4/17/2022

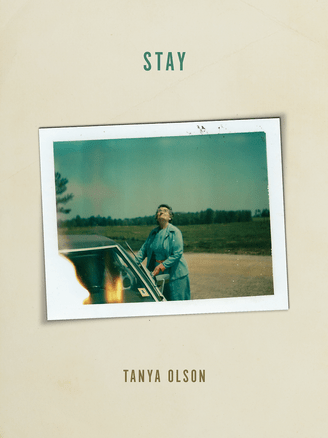

Tanya Olson lives in Silver Spring, Maryland and is a Lecturer in English at UMBC (University of Maryland, Baltimore County). Her first book, Boyishly, was published by YesYes Books in 2013 and received a 2014 American Book Award. Her second book, Stay, was released By YesYes Books in 2019. In 2010, she won a Discovery/Boston Review prize and she was named a 2011 Lambda Fellow by the Lambda Literary Foundation. Her poem 54 Prince was chosen for inclusion in Best American Poems 2015 by Sherman Alexie.

Caroline Hockenbury is a poet, journalist, and maker-of-all-things-multimedia. Her work, spanning from the literary space to the nonprofit one, is largely concerned with consumption. (In fact, she’s building a poetry manuscript around the topic.) She’s not afraid to bring questions of food justice, animal rights, and Southern identity directly to the page. Her poetry lives in LEO Weekly, The Virginia Literary Review, and Virginia’s Best Emerging Poets, and her prose can be found on Virginia Quarterly Review (Online) and in C-VILLE Weekly. Caroline formerly engineered sound for Probable Causation, an academic podcast on crime and economics, and cohosted episodes of Professors Are People, Too, a WUVA audio series. She currently resides in Washington, DC, where she is an MFA candidate at American University.

Introduction to “o camerado close! o you and me at last”

By Caroline Hockenbury

What is the ultimate stamp of commitment in a career? For poet Tanya Olson, it’s the promise to take her craft to the grave. “I am here for the long run,” she says. The artist and academic has seen her poetry gain significant momentum over the past decade and some change. Still, she has no intent of flexing her foot on the breaks or even cutting into the slow lane. If her creative journey could be packaged in a pair of words, it’d be the simple refrain, “keep going.”

Olson has framed her life around literature in many ways. In her younger days, she was lured by the gleam of academia. She recalls attending college (where she studied English) and thinking, Professors really get paid to read and write books? The occupation seemed like a dream. So naturally, she chased it—eventually securing a senior lectureship at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. When describing her trajectory toward teaching, Olson exclaims matter-of-factly, “I love books!” Hence, she leaned into higher education, relocating to Dublin for an MA in Anglo-Irish Literature and landing at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro for her doctorate in Twentieth-Century British Literature. Although Olson flexes her academic-writing muscles less these days, her previous scholarly works hone in on topics like gender and sexuality, composition, and Irish literary tradition.

As a move to Dublin might suggest, Olson is adaptive by nature. She’s no stranger to a change in scenery, having also resided in Illinois, Georgia, North Carolina, and (now) Maryland all in one lifetime. Perhaps her fascination with space, informed by her own history of boundary traversion, is the reason why she’s drawn to art “on America”—creations seeking to scale an expansive nation. Olson lists Gertrude Stein as a primary influence. “I admire the bigness of it,” she says, reflecting on the scope of Stein’s writing. And then, of course, there’s Walt Whitman’s legacy to weigh.

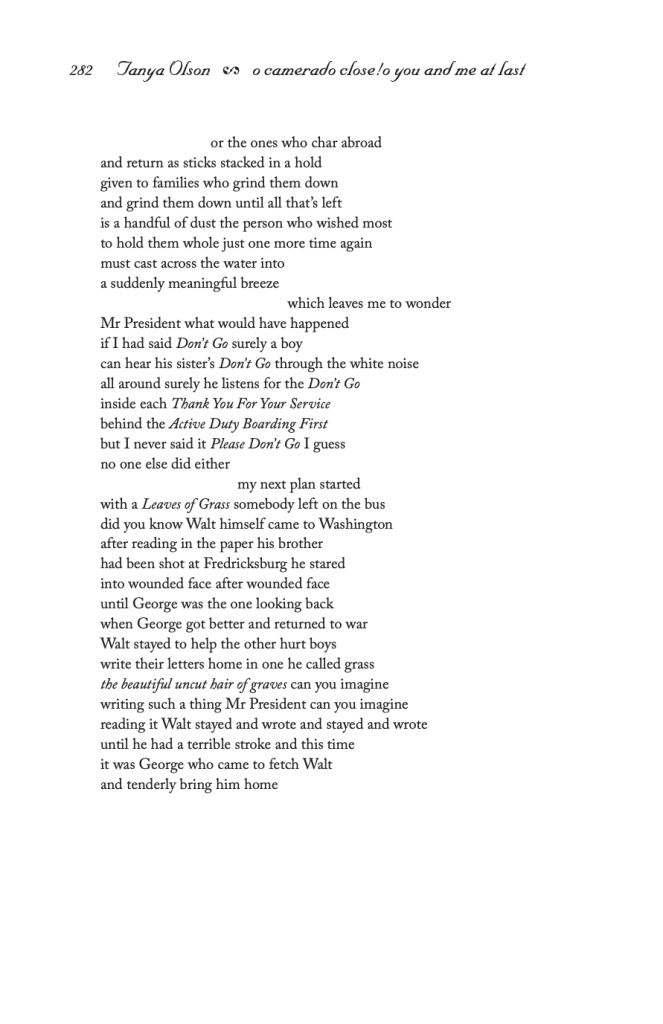

In Olson’s poem, “o camerado close! o you and me at last”—initially published in Grace and Gravity—Whitman’s legacy is a tugging presence. Take the piece’s first words: the title, drawn directly from “Starting from Paumanok.,” a poem from Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. His collected verse inspects American identity, spilling history and feeling onto the page. Certain works would even touch on the time he spent volunteering as a “nurse” in and around Washington, DC during the Civil War.

“O camerado close,” as Olson once truncated its title, is a poem to be felt as much as it’s meant to be read. Because the eight stanzas are so sincerely written and imbued with emotion, it can be surprising to learn it’s a persona poem. It’s the type of work that gives a new meaning to the word “stakes.” How much war poetry falls flat, failing to assume tragedy’s hulking frame? And, on the flip side, what population of poems successfully takes war by the horns, handling the subject deftly, rendering the reader numb? “O camerado close” is a rare and memorable achievement in this realm.

So, if this poem isn’t first-hand reflection, where’s an artist to start? How did Olson dream up lines about a fictitious person’s situation so convincingly—zeroing in on the heart of poetic truth and bending toward story? The science is imprecise but deeply informed, especially by experience and exploration. When I asked Olson whether she ever conducted research for her poetry, I learned she mainly stirs her creative pot by looking and living.

In the case of “o camerado close,” the idea flickered when Olson visited a Whitman exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery. Here, she familiarized herself with his historic stretch in DC and the surrounding area, during which he looked out for his brother and other soldiers maimed in the Civil War (“Walt”). Whitman’s influence in “o camerado close” is in some ways blatant; his direct words appear in the poem’s title and body (see “The beautiful uncut hair of graves” in “Song of Myself.”). But it also surfaces more softly, like in the repeated address, “Mr President,” which may harken back to “O Captain! My Captain!” (an Abraham Lincoln–focused poem, featured in later editions of Leaves of Grass).

Although Olson came across Whitman’s work in high school, it was later on that she experienced its magnetism more fully, “after [she] started writing.” In “o camerado close,” which is set in the Obama era, the grief-stricken poetic voice has a similar breakthrough, happening upon Whitman’s poems when they’re left behind on a DC bus. Such a detail allows Olson to lean into this persona and even establish a parallel between the poetic voice’s sibling—lost to war in the 21st century—and Whitman’s brother, George. A member of the Union troops, George sidestepped death when a blasting shell sliced into his face at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Olson also speaks to a sense of awareness she adopted upon moving near the nation’s capital. The White House, a symbol of proximity for her, became an orienting landmark. As she settled into the DMV, Olson began grappling with a new notion: living with the “seat of power so close.” She recalls the strange crawl of realization, the unshoulderable sense that “real people” labor in the area’s government buildings. Just around the bend, President Obama could be arched over his Oval Office desk. What better way to wrestle with this peculiar, newfangled feeling than taking pen to page—imagining a connection between ordinary citizen and elected official?

The result is a poem equal parts heartbreaking and artful. In it, form functions almost like waves, loosely linking associations and forming resounding currents. The second stanza establishes the pattern of hard-tabbed first lines—the initial words of these new sections lunging across the page to snag the baton where the last stanza left off. The flow is smooth yet energy infused. Take this transition, in which the poetic voice traces a teary ring around the memory of her lost brother:

at first I kept all his letters in a box

tied it shut swore I wouldn’t read them until

he came home safe turns out Mr President

he had signed each one Now You Stay Sweet

made sure he left out the ugly

mornings

I glimpse him standing there in his mirrory echo world

he tries to talk but his voice won’t work

each week he’s dimmer fading sliding farther away

Around the time of this poem’s conception, Olson also met someone whose brother—a marine—had passed, so she actively considered the shape such loss can take in a person’s life. Then, there’s the reference to Cuba and a lengthy swim, which actually opens the poem:

dear Mr President my first plan

was swim to Cuba since they were the enemy

closest at hand imagine that journey

103 miles 61 hours stingrays jellyfish sharks

Not only does such language underscore how grief can assume its own body, thick with strength, but it makes a time capsule of the era in which the poem was written. Remember Diana Nyad, the 2013 phenom who embarked on an epic swimming trip to Florida from Cuba? Perhaps only poetry could welcome this sort of memory into a broader sketch of war, national identity, and familial loss.

So why poetry, in Olson’s case? Many people who fall into the artistic discipline have a distinct origin story—a time when they saw the form spread its wings, they looked on in awe, and they wondered themselves onto the page in response. This moment came for Olson in Raleigh, after she started attending events through the local writing group Stammer. Encountering the work of her peers, she was inspired to commit to poetry writing herself. Years later, the prospect of publishing would tap her on the shoulder. “I think I have enough pages for a book,” she realized.

When the time for pitching came around, Olson remarked to her partner, “I just want one yes.” But when publishing success came knocking on her door, it brandished two affirmatives: YesYes Books’ poetry editor approached Olson after catching her Discovery Prize reading. An independent publishing house interested in the “provocative,” YesYes offers cover-bound homes to select fiction, experimental art, and—of course—poetry projects. So was the genesis of book one, Boyishly. YesYes also released Stay, Olson’s second collection including “o camerado close! o you and me at last.”

Although Grace and Gravity maintains a focus on fiction and nonfiction work, Olson was just the type of writer publisher Richard Peabody was willing to bend for. A member of the DMV’s literary community, Olson loosely knew Peabody, and he made the room for “o camerado close,” a gripping poem with a narrative undercurrent, ready to sweep readers away.

Olson has made a point of pouring poetic truths (and broader American ones) into lines. This practice will be a lifelong one. Olson even projects her own Dickinson-esque end: a loved one hovering over the desk she leaves behind, palming an unfinished manuscript, and making a silent promise to seek out its publication. Even in death, Olson will proclaim depth. She’ll “keep going”—folding poems into books; elevating queer and US experiences; and resodding the poetic landscape along the way.

The following is a selection from Abundant Grace, pages 281-283.

Click here to learn about Tanya Olson’s book Stay.